There is something Californian about the solitary house, perched right on the rocky shoreline. It looks exclusive, which it is – you would be fortunate indeed to get permission to build so close to the seafront in Norway today. Yet at the same time, Lásságámmi exudes a rustic hospitality.

The artist’s little house in Ivgobahta/Skibotn was designed by the Finnish border guard and self-taught architect Eino Jokinen from Raattama, in close collaboration with Áillohaš himself. According to Jokinen, the building’s design was the result of a process that took many years, and was based on a close friendship between the two. This meeting of minds is clear to see. For this is a house where owner and architect have undoubtedly shared very much the same ambition and vision for the project.

Lásságámmi is luxurious, though in a plain, down-to-earth sort of way: California Beach meets rough-cut pine panelling, a surround sound system on simple wooden shelves, and vast panes of glass framed by untreated Finnish timber. The lower ground floor contains a separate home spa-cum-laundry, with shower, sauna and views over the fjord. This contrast between the hypermodern and exclusive, and a sort of bold accentuation of the spartan, pared down and traditional, is the very essence of the building.

Lásságámmi can be read as a Gesamtkunstwerk: a spatialization of the soundscape, images and natural materials that Áillohaš surrounded himself with. The building is Áillohaš, not only because of what lies within its thick outer walls, but because the building is so inextricably bound to location and landscape. It is precisely here that seabirds catch rising thermals; it is precisely here that one of Sápmi’s finest gárgu (rocky beaches) starts to unfurl northward for a couple of kilometres along the Ivgovuotna/Lyngenfjord. Here, we are just a two-hour drive from his home – up in the mountains – on the Finnish side of the border. This stretch, between coast and inland plateau, follows the same line in the landscape along which reindeer herds migrate. It is a stretch that Áillohaš and his reindeer-herding family probably called home. Lásságámmi lies at the end of this line.

The spectacular plot of land was gifted to Áillohaš by Storfjord’s municipal council, ultimately becoming the location for Lásságámmi – the Turf Hut on the Rocks. It is said that Áillohaš used to sit here in this special place and draw inspiration from the birds and the weather. Could he perhaps have lived here even before the house was erected?

It is easy to read the house’s visual language. The heavy and robust rests lightly on a pale grey concrete foundation. The round shape with a vertical central space leads the eye upward, but also backward in time, with references to ancient Sámi building practices. The iconic lávvu (sámi tent) and goahti (turf hut) around whose central hearth everyone can gather, is a recurring theme in Áillohaš’s works. The visual expression becomes lighter where the veranda circles the house, held up by slim but steadfast wooden piles. Anchored in the rock, the piles stretch up to different heights before ending as outdoor lamps and birds’ nests. The long, sturdy wooden ramp takes us from the pebble beach up to the front door. The heavy, Finnish logs have been cleverly notched together to form six, strong outer walls. Lásságámmi speaks its own language.

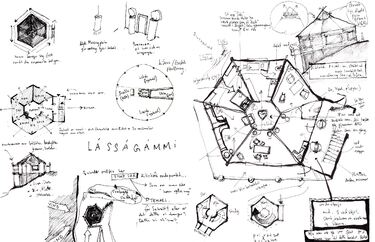

We enter the house. We are in the uksa, which is the Sámi term for the entrance to a goahti or lávvu. Two vast logs – each more than a metre in diameter – stand to attention on either side of the front door. Two “heads” balance on their flat-cut tops – two disks of sawn timber, positioned with their rings turned to face us. These are the sculptures Beaivi, áhčážan (The Sun, My Father) and Eanni, eannážan (The Earth, My Mother), which welcome us in from the uksa. The sunken stone floor is warm and the space opens up. To the left, the eye is drawn out into the landscape and the magnificent views from the three workrooms – the first for joik, the second for poetry-writing, while the third is equipped with a sink and a stone floor for heavier work with physical materials. To the right, the ancient pine forest can be glimpsed from the secluded library, whose shelves house a collection of books that reveal an artist who was both a traditionalist and a hypermodern citizen of the world. Straight ahead is the árran, or fireplace. A floor plan of the house is full of arrows, numbers and hand-written notes in Finnish. All that is drawn in the centre of this space is a heart. For us romantics, it is obvious that this room is the core, the very heart of the house. Here, the massive stone fireplace rises past two exposed crossbeams to the house’s highest point, the reahppenráigi (smoke vent), where a cone-shaped glass roof opens the room up to the sky and the Northern Lights.

The fireplace is a bird cliff. A-top it stands a grouse, and in a hollow, lie the ‘eggs’ – fist-sized round stones. The fireplace is also a “valkeapää” – a blonde head. At the very top, sits a flat, white stone. Some traces of the Lásságámmi’s first resident are obvious, some hint more subtly at who Áillohaš was. Together, they give the impression that he is still here – in the pine bark along the bookshelves, in the sculptures with their carved wood faces and majestic reindeer antlers. He stands in the corners of almost every room. He may have been a romantic, Áillohaš, and an appreciation of the romantic may be required to fully experience the house.

Slender copper lamps suspended on thin chains hang widely spaced from the ceilings of every room. They were designed and hand-made by Eino Jokinen, not just with a touch of the romantic, but apparently with a twinkle in his eye. For when night falls and the lamps are lit, they shine red. Indeed, the entire house seems to be swathed in a copper red glow when the winter darkness falls. The light from the reahpenráigi is visible from the outside. The hexagonal house, with its black roof, rises to a point as if borne up on lávvu poles. And when you stand outside Lásságámmi at night, red and green light shines out into the dark from inside. A subtle play on Sámi traditional colours also appears on the bathroom tiles, inside the toilet door – yes, even the towels and clothes pegs are red, green, yellow and blue.

The stereo system is connected to speakers in every room. You can even listen to music in the sauna! Áillohaš’s entire catalogue is available, and when we put on the drone track from Eanan, Eallima Eadni, we are transported out into Áillohaš’s landscape in two senses, through the track’s recording of bird calls, song and joik, and through Lásságámmi’s own sound picture that melts into the music. The generous windows are triple-glazed, but it still seems as though everything outside is also inside. The veranda’s balustrade is the rail of a boat and the waves pound while the storm whistles in the chimney. Translated, the name of the album means The Earth, My Mother, and listening from inside Lásságámmi is like listening to Lásságámmi.

What is Sámi architecture? One way to understand Sámi architecture is through form and tectonics, where the external and material expression references traditional Sámi culture, thereby making the architecture Sámi. Another, less nostalgic way of understanding the term is through use – put simply, all architecture used for Sámi purposes and by Sámi people is Sámi architecture.

Lásságámmi may well be Sámi architecture through tectonics, symbolism and purpose. But perhaps the house’s strongest characteristic is its ability to absorb and reflect Sámi mythology. Through the rooms’ arrangement and design, the architecture breathes life into traditions and narratives that take us straight back to pre-Christian and Sámi concepts of space.

Lásságámmi’s heart is rooted in the traditional Sámi worldview that is made up of three worlds: an underworld for the dead, an over-world for the gods, and a world in the middle for the living. A vertical connection binds the three together. At Lásságámmi, this vertical connection is achieved through the árran (fireplace), and the transparent opening that draws the eye from the flames up towards heaven, to the clouds, the stars and the Northern Lights. It links people to the spirit world. And while the árran fulfils a practical purpose – providing light and warmth – it also has an important social function. It is the very heart of Lásságámmi.

“We can choose to meet the world with clenched fists,” a wise woman once said, as she squeezed her fingers together so the muscles of her forearm stood out. “Or we can loosen our fists,” she continued, unfurling her fingers and holding up two open palms, “and meet the world like this.” That is how we are met by Lásságámmi.

With open palms, Áillohaš welcomes us in to Lásságámmi, to his universe, to the house that was his while he lived, but that now, in accordance with his wishes, is run as an artist’s residence, where selected artists and researchers working on projects relating to the Sámi and indigenous philosophies are invited in.

Giittu. Thank you. So begins and ends almost every entry in the guestbook from the many authors, artists, scholars, writers and musicians who have stayed there, all expressing their heartfelt gratitude. One musician who stayed for a week in late winter got snowed in. She sat writing melodies for three days straight, before being forced to climb out through a window to clear away the snow blocking the front door.

Through its actual use, the architecture and the rooms are opened for new encounters. We who enter are given the opportunity to share in Áillohaš’s history, immerse ourselves in his art, get to know his friends. At the same time, the house provides space to create new narratives, inspiration for new art, impetus to break new boundaries and continue to forge a path for Sámi rights and greater visibility. In this way, the metaphor of the two open palms is not quite accurate. It would be more correct to say that one fist is clenched and then raised. Áillohaš wishes to welcome people into his home, at the same time as we who enter add our efforts to the ongoing struggle for greater Sámi visibility. The house stands just as he left it, but now encompassing new thoughts, music, poetry and art. Seen in this way, Lásságámmi is still under construction. This is how Áillohaš’s painstaking work of building Sámi infrastructure will continue on into the future.

About the article authors

Joar Nango (b. 1979) is a Sámi-Norwegian architect and artist, living in Romsa / Tromsø.

Astrid Fadnes (b. ) is an architect and writer.

The article was first published in the catalog "Nils-Aslak Valkeapää / Áillohaš", Henie Onstad kunstsenter and Nord-Norsk kunstmuseum (2020)

All photos: Ingrid Fadnes