|

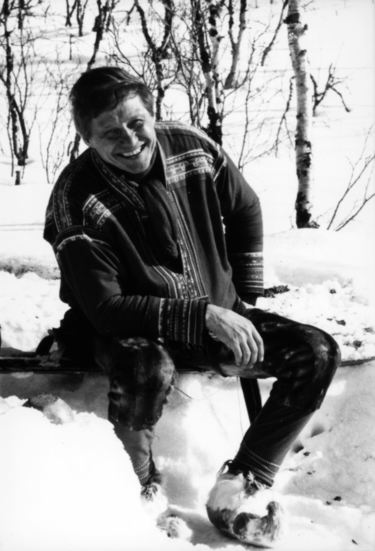

| Nils-Aslak Valkeapää. Photo: Seppo 'Baron' Paakkunainen |

Nils-Aslak was born in 1943. The family lived for a while in Ádjagorsa, a couple hours’ walk from Beattet on the road between Kaaresuvanto and Kilpisjärvi in Northern Finland. Later they settled in Beattet, and after his parents decided to move to Skibotn in Nord Troms, Nils-Aslak took over the house. His mother belonged to a family that had its summer pasture on Uløya in Troms, while his father was a reindeer-herding Sámi from the Kaaresuvanto area. Nils-Aslak felt an affinity to both areas, and kept moving between the two places. He moved to Skibotn on a permanent basis in 1996. That Nils-Aslak decided to become a Norwegian citizen and settle down in Skibotn, was very well received by the local population. The symbolic effect of this was important for the entire surrounding coastal Sami culture.

Nils-Aslak Valkeapää was educated at a teachers’ college in Kemijärvi. He chose teachers’ college not because he ever intended to become a teacher, but because it was an education that gave him schooling in a number of areas he was interested in, among others literature and music. Nils-Aslak became a renewer primarily of Sámi music, and, for one thing, created a new interest in Sámi yoik at a point in time when it was on the verge of dying out due to long-time suppresssion and stigmatization. He started by combining traditional yoik with modern instruments and popular music in the late 1960s. Later he developed yoik into an interplay with more jazz-inspired genres in cooperation with some of Finland’s foremost jazz musicians. There are still several Sámi musicians who follow this tradition. Gradually he also developed a new form of yoik that has clear features in common with classical compositions. Nils-Aslak was the catalyst behind the organizing of Sámi artists that picked up speed in the course of the 1970s. During the same period he was coordinator of cultural projects in the now defunct World Council of Indigenous Peoples, and was the driving force for the first festival for indigenous art and culture, Davvi Šuvva, in 1979, which took place in Kaaresuvanto in Finland and Karesuando in Sweden on both sides of the Könkämä River that forms the national border between the two countries.

The decade from the middle of the 1980s up to a traffic accident in 1996 that changed his life, was a hectic period for this multi-media artist. He spent a lot of time and work in order to improve the publication possibilities for Sami literature and music. During this time he together with a handful of friends established the publishing house DAT, where he was the artistic supervisor. In 1991 he was awarded the Nordic Council’s Literature Prize for his lyrical work Beaivi, áhčážan (The Sun, My Father in English translation). His pioneering music received international recognition when the so-called bird symphony, Goase dušše, was awarded the the jury’s special prize in the European radio competition Prix Italia in 1993. It is a symphony in four parts consisting for the most part of sounds of nature in Sápmi, put together like a journey from spring to autumn, from high plateaus to the sea. His pictorial art too received a lot of attention at that time; he was festival artist at the North Norway Festival in 1991, and later some of the same paintings traveled around the world to exhibitions, even as far as Japan and China.

His house Lásságámmi lies at sea level, right below the state highway going north toward Alta. It is a beautiful little six-sided house. It was intended as a home for himself and the birds of passage that he loved so much. He saw a parallel between his own travels around the world, the annual journeys of the birds, and the reindeer’s migrations between summer and winter pastures. He decorated the house himself with various sculptures that had almost become his family and that he had named according to the titles of his books and poems. At the foot of the bed in his bedroom stands “Eaidanas ealli,” that gradually became Nils-Aslak’s name for himself too. The expression appears originally in two poems in The Sun, My Father, and there it means “the animal who keeps away from the rest of the herd.”

The special thing about Nils-Aslak Valkeapää’s art is the different modes of expression he chose to use. A poem can be read in isolation, but it is best understood when it is read as a continuity, both with regard to the other poems, but perhaps just as important with regard to a yoik on the same theme or an image that accompanies the poem in the form of a photograph, a pencil drawing or a painting. It is in the totality of his expression that you understand Nils-Aslak best, but you can readily enjoy the works of art individually and have a complete experience from just that. His art was intended to be open and inclusive, in the same way that he himself was open to impressions and impulses from the outside that he allowed himself to be inspired by and used in his work. It is enough to read the introductory poems in Trekways of the Wind, where he begins by greeting the reader with “Hello, my dear friend.” That immediately gives a feeling of being welcomed and of being taken seriously for what you are, and gives the reader the desire to become acquainted with him who is greeting you so accommodatingly. At the same time the pencil drawings that accompany the text give a feeling of wandering in an expansive landscape where you finally meet a person who greets you hello.

In the same way as the different modes of expression go together and form a unity, so too was often the creation process for Nils-Aslak’s art. Occasionally it was difficult to be able to say for certain which came first: whether a yoik was inspired by a poem he wrote or whether the idea for a picture was born from the music in the words or the song of the birds that he loved. Nils-Aslak Valkeapää did not write about nature, he wrote nature itself – someone who lives so close to nature as he did the greatest part of his life has no need to describe. Therefore his poetry too has a certain directness about itself; it speaks directly to the senses, and thus expresses a genuine situation that contains so much more than just the sum of the words in a poem.

Nils-Aslak took his mission as contemporary muse seriously, and helped bring forth new yoikers and poets through practical guidance, through publications and by inviting young practitioners along on some of his many trips. He also performed his multi-media art on the stage by giving yoik poetry concerts where he read his own poems in the original Sámi, someone else presented them in English and a third person yoiked. This concept could also be extended to include instruments, and he would even paint a picture during the concert. He did that at the international exhibitions in some former Olympic cities ahead of the Olympic Games in Lillehammer. And many will surely remember his powerful yoik in the opening ceremony at the those Winter Games in 1994. Likewise it is Nils-Aslak’s yoik that set the tone in the opening scene of Nils Gaup’s 1987 feature film Ofelaš (Pathfinder).

Nils-Aslak’s last book was Eanni, eannážan, (The Earth, My Mother). It was launched at a concert on Good Friday evening during the Easter festival in Kautokeino in 2001. Nils-Aslak gave the concert as a thanks for life, for he had survived the traffic accident and could continue with his work, but it was just as important for him to give the concert to show the gratitude he felt for the Sámi people because that year he could celebrate his fortieth anniversary as servant for the Sámi, as he put it. The yoik “Sámiid eatnan duoddariid” (Samiland’s mountain plateaus) has become and will remain the second Sámi national anthem, alongside the official one. When Áillohaš – which he used as his Sámi artist’s name for a while – performed it for what would be the last time at the Easter festival in Kautokeino, the entire hall was deeply moved, and the standing ovation afterwards was the clearest expression of the place and position Áillohaš will always have in Sámi hearts. His role as ambassador was not something he had given himself, nor was he given it by any institution, but it followed naturally the dignity with which he represented Sámi culture wherever he traveled.

In The Earth, My Mother we get to know better how absorbed Nils-Aslak was in the importance of traditions for an indigenous people. The book is meant to open up to a wider perspective on the place and importance of indigenous peoples in the world, and as such it is both an extension and continuation of the prize-winning book The Sun, My Father. The Sámi stood at the center of The Sun, My Father, while in The Earth, My Mother the first person narrator goes on a visit to other indigenous peoples in the jungle and desert. The entire time it is nevertheless clear that the I person is a guest; he does not pretend that he can be one of them, but he registers similarities in values and manner of living. In Trekways of the Wind too the first person narrator was on a visit to his kindred in Greenland and on the American prairie, so in many ways it is the completion of the journey he began that we are presented with in The Earth, My Mother. And thematically there are several similarities between Ruoktu váimmus and Eanni, eannážan, not least in the criticism of civilization – it is man himself in all his self-important grandeur that is the greatest threat to life on earth. The first person poet stands shoulder to shoulder with the oppressed, and remembers in ironic expressions how the erudite and genteel people in their time used to look down on the northern indigenous people; yet they weren’t able to manage without help precisely from those they called primitive.

Nils-Aslak also wrote a play that had its first two performances in 1995 in Japan. In its Sámi original it was first staged at the Sámi theater Beaivváš in 2007 as Ridn’oaivi ja Nieguid Oaidni (The Frost-haired and the Dream-seer). In this piece he shows clearly how we are all part of Nature, how everything is tied together and how we are connected to each other. The indigenous peoples’ view that our future is dependent on our showing respect for Mother Earth, and that our attitude toward everything living on earth is reflected through our way of relating to our surroundings, is perhaps best expressed in a short and often cited poem from Trekways of the Wind:

Can you hear the sounds of life

In the roaring of the creek

In the blowing of the wind

That is all I want to say

That is all